The curatorial collaborative is a student initiative that brings together MFA and BFA candidates, as well as MA and Ph.D. Candidates in art history, allowing artists, curators, and art scholars to work together to create a final project, which is exhibited at 80 Washington Square East.

The In-between

February 12 – 16Alyx Runyon and Maya Beverly

Curated by Charlotte Kinberger

Western culture loves taxonomy for its ability to simplify and sort. But this sorting breeds boxes––both physical and theoretical, real and imagined––that we sort ourselves and each other into. These boxes become identitarian dichotomies: white/black, woman/man, servant/served. And in their overly simplistic formulation, these bifurcated boxes become cages. Through their work, Alyx Runyon and Maya Beverly explore and expand these limited categories of identity, revealing their confines and finding freedom in their interstices.

Through performative video and sculpture, Runyon makes the limitations of our binary definitions of race and gender legible. Using their body as a medium in their video works, sometimes placing it into physical danger, Runyon literalizes the suffocating sensation of failing to fit into predetermined spaces and definitions. In both their video and sculpture works, the artist uses plastic to create barriers and boundaries. Nailed to the wall or placed on a pedestal, their sculpture features organic strips or shapes of clear plastic that hold both found and made objects. Like skin, the plastic becomes a membrane and a container for symbols of identity. The transparency of plastic mimics the invisibility of identity formation in the everyday, while simultaneously allowing us to penetrate its surface. What emerges are the grey areas where our definitions disintegrate, and the self comes into being.

Just as binary definitions of gender and race break down in Runyon’s work, so too, in Beverly’s, do the distinctions between public and private space. Beverly’s exploration of domestic labor makes clear that the home and the labor performed within it contain both public and private concerns, for the politics of race and gender can never be left at the door. Drawing on ancient Egyptian shabti figures––funerary objects that were placed in tombs to perform manual labor for the deceased in the afterlife––Beverly creates small ceramic figurines as a meditation on contemporary domestic laborers. Through this alignment with an ancient African ritual tradition, domestic labor performed in the present becomes imbued with historical resonance and regal power. Her small, genderless figures reach across time and place to interrogate and trouble racialized and gendered stereotypes about the bodies that perform such labor. Similarly, Beverly’s ceramic busts explore black beauty standards, teasing out the ways in which hair and jewelry become a site of both pride and prejudice, ideal and distortion. Beverly’s subtle rendering of form causes the busts to be at once figurative and abstract, gendered and ungendered. In each body of work, the body and the space it inhabits become sites of both entrapment and emancipation. Yet again, identity finds its truest form in the intervening space.

Together, Beverly and Runyon unpack the complexity of embodied experience in contemporary life. More than ever before, our taxonomic means of understanding the world are becoming inadequate. What once were easily defined, discrete categories––public and private, male and female––increasingly breakdown under scrutiny. What remains is the space beyond the bounds: the inbetween.

Cellar/Attic

February 19 – 23

Hue Bui and Monique Muse

Curated by Blake Oetting

Few things are as riddled with cliché as the home: “Home is where the heart is,” “a house is not a home,” and “home is wherever you are,” all being examples. These sentimental truisms, among many others, substitute a structural definition of a household for one that is immaterial and transitory. Defining the home through nebulous matrices of familial relationships, biological or chosen, rather than by physical site implies a disavowal of objects, the things of home that constitute its notional resonance. In Cellar / Attic at 80WSE, artists Hue Bui and Monique Muse have collaborated on an installation that foregrounds precisely this material element of home-making.

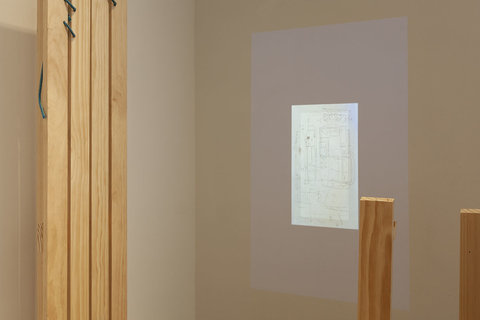

Cellar / Attic includes two works, which––to quote the artists––form a “spatial composition,” eschewing relationships between adjacent walls to engage the gallery’s vertical axis. Muse’s contribution, a large wooden sculpture, is situated beneath a wire armature made by Bui; a nest that supports a network of lights, printed ephemera, and fabric. To a certain degree, the artists’ individual contributions are split between the upper and lower registers of the gallery. However, because Muse’s sculpture operates as a functional bench for visitors, its seating angled to produce a sightline to the ceiling, she directs attention upwards. Conversely, while the skeleton of Bui’s work resides overhead, its constituent elements cascade down and engage the ground. In creating a dynamic, inchoate relationship between “cellar” and “attic,” up and down, Bui and Muse foreground their spatial entanglement.

Despite the connective tissue created between Muse and Bui’s sculptures and the consequent production of a single environment––a space for sitting, looking, communing––each artist’s work describes particular relationships to home and home-making. Muse exhibits a concern with meticulous engineering. Because her sculptures are often functional, either as recognizable domestic furniture or as less legible platforms for reprieve, a certain technical mastery is required. Having lived in many different homes with her family while growing up, Muse notes an “undeniable urgency” to fabricate furniture as a means of grappling with her sense of being permanently in transit. Bui, who grew up in Vietnam, works within a similar epistemological uncertainty with respect to home. The wire apparatus that Bui has constructed for Cellar / Attic refers to a lotus leaf, Vietnam’s national flower. The form Bui constructs, with its undulating curvilinearity, materializes her “looped” relationship to time and memory, her “then, there” constituting her “here, now.”

Bui and Muse, while articulating these subjective and distinct approaches to home, ultimately engage in a dialectical relationship with each other in Cellar / Attic. Subsequently, the physical environment in which their work participates suggests a type of coalition––a warm embrace––between each other, with viewers, and with their materials.

Tracing History Through Myth

February 26 – March 1 Martine Velasco and Andy Wang

Curated by Katie Maher

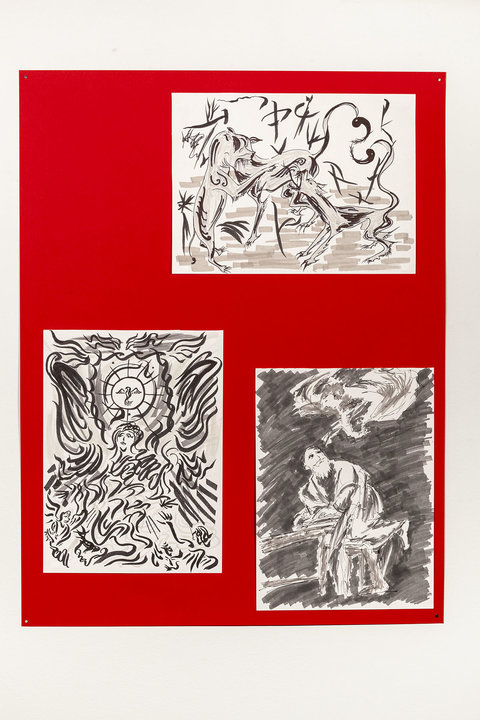

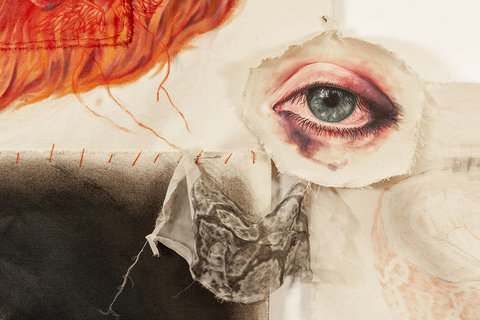

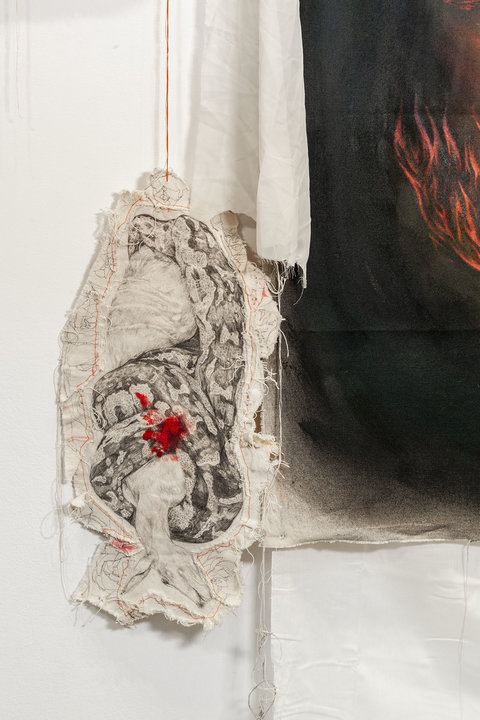

From a technical and stylistic perspective, Martine Velasco and Andy Wang’s practices could not be more distinct from one another. Their shared interest in historical themes and myth-making, however, is strikingly parallel. Wang and Velasco’s works respond to an innate human desire to understand what links the old and the new. Fusing their own familial and cultural ties with historic elements, both artists explore themes of transformation through their work.

Wang and Velasco’s mutual interests in historicity manifests itself in ways that speak to each artist’s cultural backgrounds. Wang’s colorful, carefully rendered drawings and earthenware ceramics illustrate his curiosity towards historical themes. He demonstrates a fascination with ancient Chinese and Greco-Roman traditions. The interplay between past and present in his work challenges him to retain his own artistic identity while exploring historical themes. Velasco, on the other hand, relies on ritualism in order to incorporate the past into her work. Her practice consists primarily of creating large-scale works on canvas, giving her pieces a raw and authentic quality. Experimenting with oil, charcoal and colored pencil on canvas, she employs repetitive and intuitive motions in order to achieve a sense of security in the physical gestures of her practice. Through Velasco’s incorporation of ritual and Wang’s implementation of historical motifs, both artists engage with the past as a means of juxtaposing it with the present and anticipating the future.

Both of these artists reference their respective cultural traditions as a basis for their artistic styles. For Velasco, Filipino folklore carries significant weight in her practice, while Wang weaves traditional Chinese elements into his multi media works and ceramics. Velasco’s painting ASWANG (2018) utilizes mythology as a means of exploring her cultural identity. ASWANG refers to a Filipino folklore villain, which not only demonstrates her interest in incorporating Filipino tradition in her work but also aligns with her tendency to include symbols of evil throughout her practice. Wang’s ceramic piece Ding (2019) refers to a type of ancient Chinese cooking vessel, and is decorated with reliefs of monsters in accordance with Chinese tradition. Velasco and Wang each incorporate monster motifs in their work to ground their practices in cultural iconography, mythology, and spirituality.

While both Velasco and Wang confront myth-making from the lens of their own individual cultures or experiences, they also share a joint interest in Greek mythology. Velasco’s choice of Venus as a central motif for Origins of a Goddess (2019) speaks to the artist’s fascination with Western mythology, which complements the Filipino cultural references that permeate the rest of her work. Wang also incorporates a mixture of Asian and Western motifs into his practice, adopting a distinctly Chinese approach to European subject matter. Through alluding to ancient Greco-Roman mythologies, Wang and Velasco demonstrate a keen awareness of Western artistic traditions. By mining their respective heritages, these two artists have created bodies of work that reflect both their own constantly evolving identities as well as an affinity for tradition.

Beyond Objects

March 4 – 8 Mika Lee and Hannah Park

Curated by Cindy Qian

The exhibition explores the presentation and representation of ordinary things that usually do not get a second look. Mika Sarina Lee and Hannah Park manipulate common materials usually used in interiors and construction sites, and combine them with conventional artistic media in their works. Incorporating materials such as glass, paper, stone, bolts, hooks, nails, furniture fragments, and more, the artists deconstruct found objects and endow them with new meanings through the manipulation of their materiality and placement.

Inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s use of glass and Constantin Brancusi’s sculptures, Lee combines fiction and reality into her intuitive drawings. Lee’s pen on paper drawing is her point of departure, functioning as parts of her collage behind glass or as the basis for her multimedia objects. Often inspired by little things she finds in curious settings or places, Lee cherishes the unique quality of found objects and places them in her work in such a way that the objects are not overshadowed. In one of her latest works, she uses laser to incise fine lines onto a piece of found limestone, combining the thin contours in her drawings with ready-made objects. Interested in disrupting people’s process of seeing, recognizing, and understanding, Lee creates works that are done with precision and delicate details that require close looking.

Also employing a wide range of materials and ready-made objects, Park explores the desire and need for “maintenance.” She describes the process of maintenance as “breaking down or emptying out, building up or filling in,” a sequence of gestures required for both the well-being of the human mind and everyday objects. The laborious process of fixing things is crucial to Park’s work. Her sculptures and installations are often created through intense manual labor of piecing broken things together and adding joints (such as hooks and bolts) to put other parts on the existing objects. Park uses the physical space and ready-made objects as metaphors, linking the human body with the materiality of her found objects. Drawing inspiration from her identity, childhood experience, and woodworking, Park constructs sculptures, installations and time-based media that capture and document the gestures necessary to maintain the wholeness of a found object or one’s mental state.

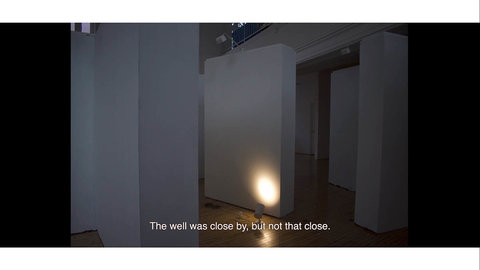

The Life of Objects

March 11 – 15

Chanel Khoury and Christine JiMin Park

Curated by Andres Gonzalez

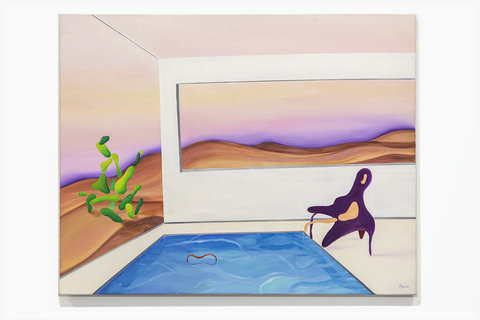

Chanel Khoury and Christine JiMin Park have been, until recently, engaged in refining the medium of paint. Their languages of painting bring abstraction and figuration into play. In some respects, they stand back to back at the center of this spectrum looking outwardly. Khoury paints perspectival environments that are often illogically constructed and open into a never-ending horizon. Park paints memories and their decay, pulling from childhood photographs. A philosophy student, Khoury’s paintings are in dialogue with a panpsychic perspective, which acknowledges a universal consciousness of objects. Her painting’s technical and stylistic cues resonate with Surrealist painting and mid-century furniture, but she does not treat these references as innocent. Her forms communicate their often-flickering mental state by quivering between supple and calcified. Khoury pushes us into her unfamiliar world by fragmenting narratives and bodies, evoking a tension between mental states and bodily positions. Park, on the other hand, brings us back to the familiar world of childhood, or the faded image we have of our childhoods. In order to make sense of that decay, she connects memory to the particular place that produced it, a concept which springs from Debordian psychogeography.

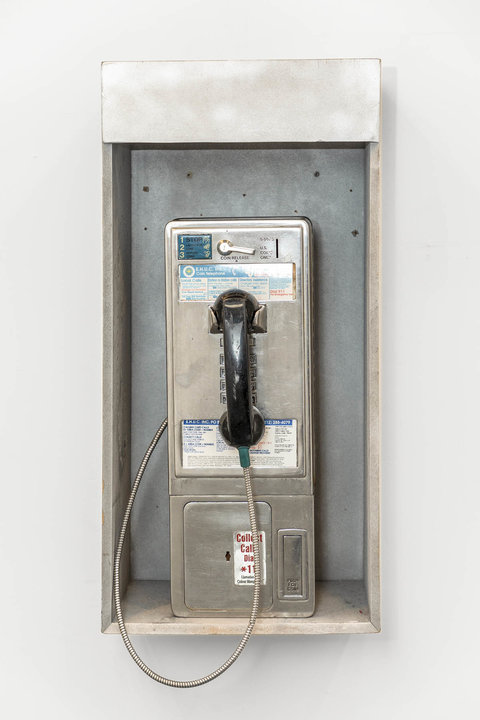

For this exhibition, both artists have expanded their practice into sculpture. Khoury’s sculpture further investigates the psyche of objects by transferring writhing forms and uncanny pseudo-narratives from her paintings. While Khoury has launched into a project of assembled sculpture, Park favors the found object, and turns to sculpture by way of her interest in sound. Park’s objects undergo the same play of (de)formation which she has previously deployed on photographs. Park carefully allows her objects to evoke their previous life. Familiar 20th century artifacts, such as a payphone, evoke the places where we have previously seen them; anonymous street corners, bus stations and hospitals.

Park seeks to rescue the obsolescent and re-situate contemporary relics in our lived space. Through techniques like laser engraving or electronic refurbishment, Park welds her personal narrative onto the object’s own geographical evocations, refuting their previous, everyday anonymity. The dangling shoes of Park’s larger installation pull the viewer into the work’s narrative, through the fragmented verses lasered onto their soles. Park asks us to consider the places and events our shoes have seen by juxtaposing composed and found text without identifying either. Both Khoury and Park look to extend the horizon of the object, beyond something that “is seen” passively to something that has active agency. They do not, however, intend to threaten our subjectivity but rather point to the way it is conditioned by the things we wear, how we communicate and the spaces we inhabit. The objects in this show incite meaning through a network of memory and empathy with the objects that have helped shape our material reality.