The curatorial collaborative is a student initiative that brings together MFA and BFA candidates, as well as MA and Ph.D. Candidates in art history, allowing artists, curators, and art scholars to work together to create a final project, which is exhibited at 80 Washington Square East.

The Universal in the Personal

February 3 – 6David Ma and Caleb Williams

curated by Juul Van Haver

During the recent pandemic-induced isolation, a mass trend of personal reevaluations of the self occurred, resulting in an almost mystifying revitalization of personhood in the midst of a global crisis. This dynamic interchange between the individual and the global is the central theme of The Universal in the Personal. In this exhibition, Caleb Williams’ and David Ma’s artworks harness each of the artists’ personal backgrounds as a means to investigate global issues such as ethnicity, injustice, and origin. The juxtaposition of their work uncovers how personal stories can have a healing effect on a broad audience.

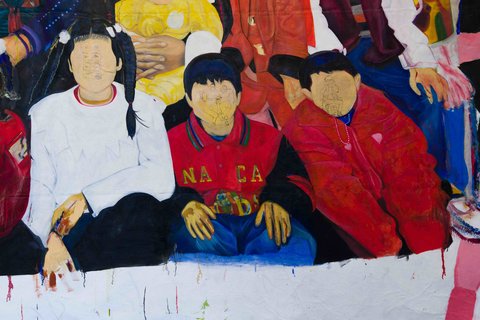

Caleb Williams grew up in Queens, New York, which deeply influences her art practice. Art offers her a strategy to define the sometimes hazy contour of the world. In Williams’ multimedia practice, she explores themes such as the social injustice against the Black community, vulnerability, identity, and the reclamation of the body. In a parallel engagement with origins and identity, David Ma grew up in Queens and Virginia, and addresses issues surrounding Asian representation in his videos, paintings, and ceramics. In his own words, his art is about “people, place and their materiality,” and how these concepts interact to shape human experiences. Williams and Ma both question where to locate their diverse cultural backgrounds, yet these friends work side-by-side in NYU’s Steinhardt studios.

The exhibition functions as an inverted archeological practice which displays contemporary material artifacts––instead of ancient material culture––to deal with the past through the present, with one eye on the future. For example, David Ma’s Selfless Family/ Selfish Boy copes with his family history and expectations, thereby opening a path for the future. The blank faces represent Ma’s understanding of the Chinese cultural conception of the family combined as a single unit, instead of a collection of individuals. Moreover, the overwhelming number of figures emphasizes the judgement of his family, and society in general, for choosing a career in arts. Works like Selfless Family/ Selfish Boy explore a per- sonal chronology within the internal excavation of the self.

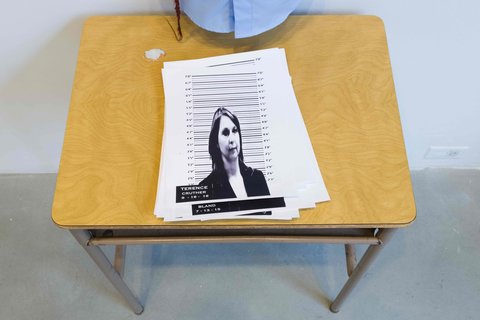

Although some of Williams and Ma’s artworks can seem monumental in both form and content, they actually interact with the beholder on an intimate level, dragging the viewer into the personal world they create. In the video The Ending of the Cycle (2021), images of Williams’ spiritual cleansing by bathwater are superimposed with images of the church where her family grew up in South Carolina. Williams seeks to come to terms with her own generational trauma, while inviting the viewer to carry a piece of her burden and become part of her personal narrative. This video work uses storytelling as a method to alter how people think about intergenerational trauma and the healing journey in order to change it one step at a time.

Through a range of media including video, painting, sculpture, and photography, these deeply personal works transcend their specificity to carry a universal, cross- cultural meaning. Through mythical colors and forms, the works touch upon real and critical social questions. Although the exhibition is embedded in the contempo- rary world context, Williams and Ma look towards a future of gradual healing.

We Used to Hold Hands in the Corner

February 10 – 13

Sarah Goldman and Nina Molloy

curated by Barbie Kim

A painting can often convey tales, memories, emotions, and limitless perspectives. We Used to Hold Hands in the Corner sees the physical form of painting as a means of narrative, emphasizing materiality and telling stories from a cosmic view. The paintings are generated from both artists’ subconsciouses; once transcribed onto a surface, the paintings take on a life of their own and cannot return to the nebulous state from which they came. While Goldman and Molloy have different processes, the artists’ work initiates in the same space through connection with material. The titular phrase We Used to Hold Hands In the Corner describes an abstract feeling the artists believe their paintings convey.

Molloy works in architectural layers of paint. She embeds her cultural heritage and personal stories in the alternative spaces of her composition. Astor Place Tree illustrates Molloy’s relationship with painting. By depicting specific objects and sites with which she shares a personal connection, such as a tree in New York, she makes these interconnections concrete. The works take on a life of their own and proceed to be ever-expanding with new layers of narrative. The flat surface of the physical painting is contrasted by the fullness and vibrancy of the subjects.

Goldman’s painting conveys the product of an organic collaboration of the artist’s body and the paint. Also working from her subconscious, Goldman’s paintings emphasize elusiveness both visually and conceptually. The painting Tree of Life II shows how the process of abstraction embodies the artist’s extension of self. Goldman builds a body of paint by thickly layering wet paint onto wet paint. The wooden panels create a nuanced color and textured pallet. Goldman uses her body to carry paint and her subconscious onto the surface, giving the work a life of its own.

Both Molloy and Goldman encourage the viewer to project themselves into the work. The painting process is slow but nurturing to the artists, connecting the physical body to the paint. Interpretation of the works makes the private realm public through rendering space. The differing styles of the artists create a harmonious visual contrast from two opposite ends. Molloy’s representational approach and Goldman’s abstract execution together entail how pigmented material can activate beyond bodily experiences and extend to a feeling words cannot deliver.

The paintings transcribe and shift their meaning through time and space. Goldman and Molloy both speak to a private consciousness that is not limited to intention and the work itself. The exhibition considers how to interpret the relationship between meaning and works of art themselves. Goldman and Molloy show that a painting can create a space extending beyond the physical canvas. More- over, the painting builds a life of its own and continues to transform the viewer’s perception. The voice of their painting speaks to the infinite connection and possibility that extends between space and reality where the paint- ing is not constrained by its surface or time.

In Search of Vibrant Matter

February 17 – 20

Brock Riggins and Rhea Barve

curated by Eve Sperling

Artists Rhea Barve and Brock Riggins examine interspecies relations and explore slow processes that exist at the intersection of time and material, such as mold, decomposition, and over-growth. Curiously, these processes simultaneously evoke a sense of decay and a sense of new beginnings, a contradiction that aptly characterizes In Search of Vibrant Matter. Working in traditional mediums like clay and paint, as well as digital formats like video and 3D image capturing, Barve and Riggins establish a relationship to the land that is essentially poetic and without a specific end goal. Their interest in subjectivity, technology, and biology comingle to lively and timely effect.

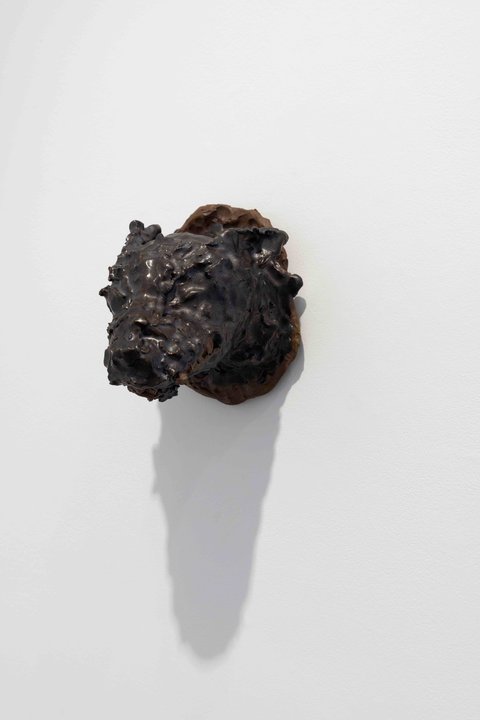

Rhea Barve’s ceramic objects can be seen as representations of fungus or Anthozoa as well as models for large, all-encompassing environments. They are inherently mutable. Due to their multi-readability, these sculptures elicit both macro and micro environmental phenomena: they play out their imagined ecologies on the scale of massive geologic formations as well as small, algae-filled, tidepools. The clay exposed by the uneven application of glaze recalls the alchemical processes that turns this fine-grained soil into objects able to endure the passage of

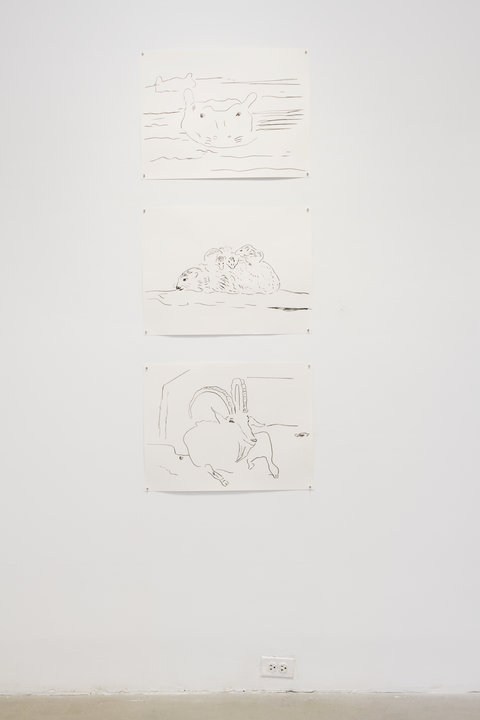

thousands of years. Their varied surface texture and colors invite the touch of curious hands, like those that reach for mussel- covered rocks on the beach. A captivation with narrative aligns Barve’s sculptures to Riggins’ paintings. In Barve’s case, the narrative constructed is one that unfolds over millions of years as organisms coevolve and become intertwined. Brock Riggins’ paintings, on the other hand, are concerned with

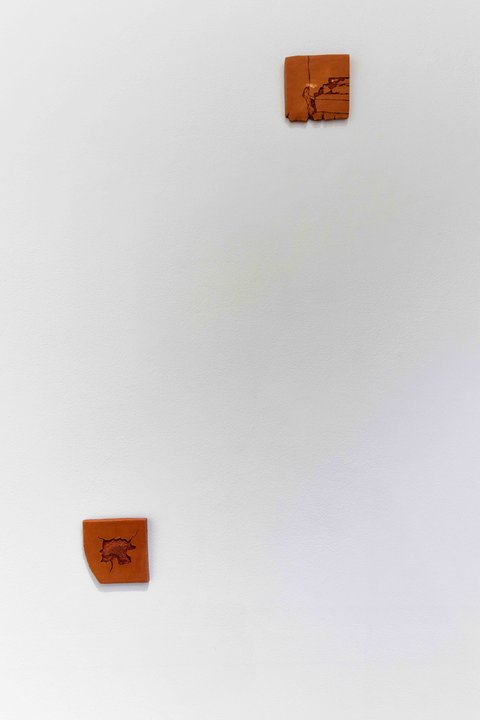

the interweaving of personal narrative and imaginary space. Taking architecture, contamination/ruin and the non-human as his primary subjects, his works are activated by contemporary climatic anxieties. The exposed canvas edges and visible graphite marks foreground Riggins’ concern with the materiality of his work, extending the theme of spatiality into the gallery itself. Conversely, his jarringly direct portraits of animals utilize clear and simple forms to evoke the idea of the animal depicted more so than the reality of it. From the earliest cave paintings, representations of animals have always figured into the experience of being human; these drawings engage with that lineage and explore the theatricality of animal encounters.

Barve and Riggins’ collaborative video work, Herauszufinden (2021), presents a fragmentary and disjointed relationship to

the landscapes that surround them. A wide array of footage is combined within the film––clips of manicured New York City parks, intimate explorations of Barve’s ceramic objects, and found footage––highlighting sensuous experience over definitive understanding. There is a complex relationship between the variety

of image capturingmethods employed in the film (video, 3D scans of natural objects, 3D scans of objects representing natural objects), which blurs the line between representation and reality. The audio accompanying this imagery comprises of a conversation between the two artists that touches on the subjects of colonialism, religion, and agrarian practice in tandem with personal anecdote. The combination of disparate video sources along with the historical and personal narratives introduced in the audio, resists understandings of the environment born from singular perspectives (whether those be economic, historic, scientific, or spiritual). Instead, Barve and Riggins posit an engagement with the environment that is mindful of its complexity and grounded in the experiential.

Art of the In-between

February 24 – 27

Delia Pelli-Walbert and Kris Waymire

curated by Allison Carey

Our society is largely defined by binaries. Humans tend to split the world into succinct, oppositional categories: man vs. nature; order vs. chaos; good vs. bad. We avoid nuance, settling for rigid categorization over uncertainty.

Kris Waymire and Delia Pelli-Walbert boldly reject this trend through their artmaking by embracing the undefined middle areas thatshape individual realities. Their work flourishes in the unknown– the gradations and in-betweens that are typically overlooked.Through sculpture, Waymire and Pelli-Walbert acknowledge the “grey area” that falls between traditional groupings. As a Native artist, Waymire questions where their identity exists in the world, or if a space for it exists at all. The artist’s sculptures combine opposing aesthetics into cohesive objects. Vibrant colors coalesce with minimalist forms; rigid edges transition into smooth curves; refined details embrace monumental scales. A work like Untitled, for example, is bold, yet delicate; assertive, yet contem- plative. Waymire’s sculptures celebrate their lack of categorization, manifesting the complex and sometimes conflicting identities that define both the artist and the viewer—which largely fall outside of clean binaries.

While Waymire’s sculptures embrace abstraction, Pelli-Walbert constructs readily recognizable objects: a teacup, a vase, an animal head. However, the materiality of her sculptures is unorthodox. Clean porcelain is manipulated to spill down the edge of a pitcher, confusing our notion of the usually rigid materiality of ceramics. The clay bust of a bull is uneven and worn; the animal’s mangled appear- ance is counterintuitive to the strength it typically connotes. Pelli-Wal- bert pushes her mediums to new limits, redefining the

represented objects into ambiguous, less clear versions of them- selves. The artist reminds us that even though something may fit a certain label, its structure can fall outside of usual conventions. The “who” can be less easily defined than the “what.” Neither Waymire nor Pelli-Walbert shy away from demonstrating the physical struggle with their materiality. The hand of the artist appears throughout each work in the form of textured fingerprints or bold strokes of paint; Waymire and Pelli-Walbert trace a battle between their vision and their material’s strength. Through these remnants of the creative process, we can bear witness to the complicated undertaking and endurance involved in navigating opposing forces.

Once fabricated, this middle area is powerful. By working in sculpture, both Waymire and Pelli-Walbert physically insert their new narratives in the world. At times, this interjection is overpower- ing. Hella Gay’s massive scale and vibrant colors demand a viewer’s acknowledgement, making us feel minuscule in its presence. Contrarily, works such as Chamber 1 rely on close attention and patient consideration; its presence and meaning are

only noticeable to those who

look closely.Sharing the same confines

as the idiosyncratic works on display, we can reflect on the overlooked in-betweens that shape each of our individualities. In a space that denies polemic binaries, we have the opportunity to consider our own middle-areas that lack definition, but that Waymire and Pelli-Walbert prove we have the power to create.

Make Space / Give Place

March 3 – 6

Talia Deane and Ebony Joiner

curated by Madi Shank

Talia Deane and Ebony Joiner’s material practices reflect on the impermanence of existence and their attempts as artists to subvert the transient qualities of lived experience. In Make Space / Give Place, both Deane and Ebony explore these themes while disrupt- ing the traditional understanding of what belongs in gallery spaces. Their work prompts the viewer to ask the questions––are we capable of accessing our past through our memories? What possibilities unfold when something is made ruined from the start?

Deane explores the idea of “ruin” as a means of challenging expectations about value and utility; they are interested in the ways decayed structures resist definition by acting as “third spaces” between inside and outside, man-made and natural. Their site- based installation Ruined explores clay as a material that retains evidence of the erosive and cumulative effects of manipulation. Carefully assembled chains of clay emerge from a crumbling site of ceramic tile, found brick, and organic debris, prompting the viewer to let go of assumptions about the structure’s functionality. Deane’s combination of raw, fired, and rust-treated clay allows them to diminish their artistic autonomy, leaning into the instability of the material as a means of preserving its agency. Deane aims to radically shift the viewer’s expectations for how and why humans make things, given the understanding that everything will inevitably fall to ruin. Deane’s artwork embodies an unmanipulated form, uninhibited by preconceptions of how the material should take shape.

While Deane activates the innate power of matter, Ebony carefully manipulates material and images to explore her identity and the ephemerality of memories. For Ebony, it is important that her work embodies her memories as honestly as possible, avoiding aesthetic edits that misrepresent the spaces implicated by her work. In Liquor and Lotto, Ebony invokes personal memories by recreating the façade of a reoccurring site from her childhood. Liquor stores, while harboring pleasant associations with the people and spaces from her youth, are generally places of disinterest and abandonment that stand in stark contrast to the gallery setting. Red letters reading “Liquor and Lotto” make the constructed façade immediately recognizable as a site of American life; yet it is only a facade. Just as one recalls their memories but cannot reenact them, Ebony replicates formal aspects of a place from her past without allowing physical access. The artist further emphasizes this inaccessibility by placing two large-scale drawings of her family members within the space of the “liquor store.” The true-to-life size of the figures and the extreme detail of their rendering implicate the observer, while their placement limits clear viewing.

In Make Space / Give Place Deane and Ebony both deal with the transience of memory and physical space by subverting static under- standings of what constitutes something that is finished or ruined. By resisting their assumed function, Ebony’s works prompt the viewer to reconsider what makes an object or space accessible, while Deane’s work explores the value and fullness that can be found in ruination.