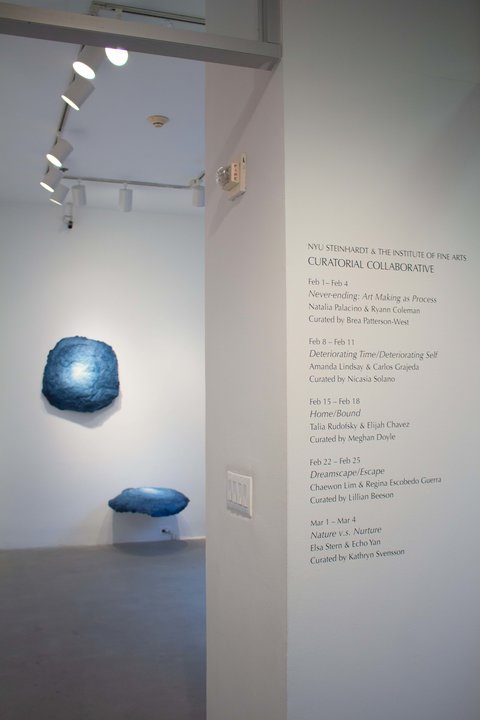

The NYU Curatorial Collaborative began as a student-led initiative in 2014, designed to pair graduate student curators from the Institute of Fine Arts’ MA and PhD programs in Art History with rising seniors from the Steinhardt School’s Department of Art and Art Professions BFA program in Studio Art.

The NYU Curatorial Collaborative fosters interdisciplinary teamwork that prepares both the artists and art historians for future projects in their respective fields. Each year, the Collaborative hosts five exhibits at 80WSE Gallery featuring student artists from Steinhardt’s Senior Honors Studio, each curated by one Institute student.

Exhibitions on view:

Wednesday–Saturday, 12–6PM

Opening receptions:

Wednesdays, 5–7PM

Never-ending: Art Making as Process

February 1– 4Natalia Palacino & Ryann Coleman

Curated by Brea Patterson-West

“Growth imagines its opposite is decay. As if to grow is to stay alive, and other delusions taught by capitalism. In reality, most of our lives are spent shrink- ing, eroding into bits and decaying. What if we celebrated that decay and championed the infinitesimal?” – Samantha Hunt, The Unwritten Book: An Investigation

The processes of art making are in many ways similar to the processes necessary to sustain our human condition – to sustain the Earth on which we are necessarily grounded. Like the very beginnings of life and death, the process of making, of creating, is imperceptible to the viewer, who only perceives the symbolic birth of an artwork at the time of its exhibition. The labor of art making, the real naissance of creation, begins far earlier. Where exactly does process begin and end? Is death a singular, isolated occurrence? Are creation and death as paradoxical as we perceive them to be?

Never-ending: Art Making as Process explores these questions without resolving to answer them neatly. Rather, the answers lay in the materials, the experiences, and the psyches of every artist and every view- er. Ryann Coleman and Natalia Palacino are two young artists devoted to process rather than medium.

Ryann Coleman describes her creative process as “cathartic and highly personal.” Drawn to the inner workings of the psyche through Freud’s understanding of the ego and the id, one could interpret her sensorial creations as a crossroads between the artist’s conscious and subconscious mind. If this is true, then the playful masculine figure that persists through many of her works might also be seen as a guardian of this intersection. Favoring popular materials like glass, neon, and vintage surf magazines as her primary mediums, Coleman’s affinity for 90s skate culture, MTV, and Nick at Night, come alive in her larger than life sculptures and installations.

Natalia Palacino’s practice exists on the opposite end of the spectrum. Her practice is deeply rooted in reflection.

There are many layers beyond the self in which Palacino situates her artworks – in nature, language, and systems far beyond individual control. Working in performance, video, painting, textile, and installation, she investigates the truths of the world we collectively navigate, often hidden beneath layers of colonial, patriarchal, and capitalist programming. Drawing on her experiences navigating life in her native Colombia, and in Manhattan, Palacino thinks through body politics, intergenerational grief, and decay.

Coleman and Palacino’s diverse multi- media practices challenge them to explore feeling and expression through materiality and processes of making. Despite their visual dissonances, together the artists’ works encourage viewers to think beyond the surface and toward the generative connectivity of process as a space of world making, where the processes of birth and death inevitably intertwine.

Deteriorating Time/Deteriorating Self

February 8 – 11Amanda Lindsay & Carlos Grajeda

Curated by Nicasia Solano

Deteriorating Time/Deteriorating Self explores the subjective nature of time, and ways in which the self deteriorates throughout the duration of life cycles. Conceptually inspired by global cultural engagements with death, this exhibition seeks to dispel notions of deterioration as synonymous with permanent loss and melancholia. While acknowledging the intangibility of time and ever-shifting essence of the self, the exhibition highlights work bringing form to these themes. Deteriorating Time/Deteriorating Self features the photographic, sculptural, and performance work of Amanda Lindsay and the paintings of Carlos Grajeda. Lindsay and Grajeda bring visual language to their questioning of how to render time and the self as concrete fixtures within their inherent deterioration.

Lindsay’s artistic practice rejects aesthetic consistency while remaining heavily rooted in art historical and political theory. In addition, Lindsay incorporates lived experience growing up on the South Side of Chicago. In their photo series titled Dibs, Lindsay captures the technically illegal, but popularly accepted practice of claiming “dibs” on parking spots after one digs their car out after a heavy snowfall. Dibs are marked with an array of objects, ranging from lawn chairs, to plastic playground equipment. Rather than specifying ownership of the physical location, the dibs mark the time and effort one spent creating their spot. As the snow melts, dibs are removed, and the spots become public again. Through the mutually accepted edifice of dibs, time becomes visual, and its subjective but deteriorating worth is respected.

In an installation of Mason jars containing urine, Lindsay contemplates the control, or lack thereof, we have over our bodies. The jars are intended to hang in front of a lightsource to emphasize the varying shades Lindsay accomplished through only consuming specific beverages on specific days. In a study of both time and self-manipulation, the jars call to mind that bodily control and autonomy both decline with age.

Grajeda works in paint, playing with scale and exploring combinations of photorealistic figuration while incorporating pop-esque design elements. Grajeda bases many of his works on found photographs from the mid-20th century. Resulting paintings take on the aesthetic qualities of vintage film, but subvert these referents through the inclusion of alterations to the environments and figures. Surrealist qualities are abundant as bodies are fragmented. In Grajeda’s large-scale painting shown in the exhibition, the subject’s face is distorted, asking viewers to consider their personal interpretations of humanity, noting that we never view other humans without subjectivity. The subject vaguely resembles a number of historical figures, emphasizing the instability of identity. In utilizing old photographs with unidentified figures, Grajeda freezes moments in time, reinterpreting the otherwise deteriorating aspects of the photos and subjects.

Both Lindsay and Grajeda center the body as a visual anchor of the self in their practices, whether it be explicitly present or not. Time is paused in their various engagements with photographs. Time and the self’s deterioration is given tangibility in their works, presenting an opportunity to ponder the otherwise fleeting concepts.

Home/Bound

February 15 – 18

Talia Rudofsky & Elijah Chavez

Curated by Meghan Doyle

Notions of ‘home’ clutter the cultural discourse, ranging from The Odyssey’s inclusion on school syllabi, to corporations targeting the domestic consumer, to the classifications of artists into geographic categories. In a post-pandemic world, even the historically separate work sphere can now invade the home, amalgamating personal with professional. ‘Home’ is so frequently associated with safety, nurture, and rest that we colloquially refer to it as ‘the nest.’ But this enduring narrative of ‘home-as-comfort’ is incomplete. Where is the chapter in which home, for all its implied welcome, deteriorates? What happens when the building still stands, but the internal systems fail?

If the self is a product of tangled, shrouded personal histories, then Elijah Chavez and Talia Rudofsky pick apart these ancestral threads, invoking the latent cultures in their respective homes as foils for their own identities. Chavez’s Ofrendas (2020/22) and Rudofsky’s Kippah (2022) betray thick spiritual trusses undergirding the artists’ current experiences. Each artist navigates this disquieting liminality; an in-between- ness that slips through the cracks of their heritages’ infrastructures. When the untangling is done, they are left with frayed remnants rather than clear patterns. Inherent to interrogation is the potential for unwanted discovery. Chavez’s and Rudofsky’s explorations threaten to reveal the inadequacies of systematized culture, reconstructing ‘home’ as a set of ties that only bind, while begging to be broken.

In Monachopsis (2018/2022), photographs from Chavez’s personal archive dangle from suspended branches scavenged from his New York City environment. The titular reference to an out-of-place sensation echoes throughout the pictures’ cutout silhouettes, emptying the space originally inhabited by the artist. Balanced atop a secular altar piled with Chavez’s accumulated ephemera, Monachopsis paradoxically writes Chavez back into his Catholic upbringing and familial roots by affirming his queer and artistic identities, solidified upon his escape to urbanity. Rudofsky’s own sense of self came into relief after leaving her native London, where soccer represented a distinctly male extra-curricular activity. He Kicked It Through the Wall and Now What Are We Going to Tell Mum (2022) acknowledges the heteronormative soccer culture, while questioning more broadly the consequences of breaking with tradition. How do aspirations beyond those prescribed by home accord with the creators of that space? How do we relate to the people who raised us when we are not who they want us to be?

Distance lets us see ourselves more clearly. For Rudofsky, the ubiquitous American Craftsman-style house defines the unforgiving mold of imposed personhood – cookie-cutter homes produce cookie- cutter personalities. Lit from within, however, Rudofsky’s Birthright (2022) cross-examines a common practice in her Jewish heritage as potentially harmful and physically traumatic. Indeed, unchecked cultural assimilation risks overtaking the self entirely – in Chavez’s Wasteland series, the artist obscures his face with an unseeing reflection of New Mexico’s desolate landscape. Still, in wrestling with their pasts, these artists find a way forward: Rudofsky’s paper assemblage and Chavez’s ceramic footprint recall the indelible marks we leave on the places from which we came, yet reassure us that we are not there anymore.

Dreamscape/Escape

February 22 – 25

Chaewon Lim & Regina Escobedo Guerra

Curated by Lillian Beeson

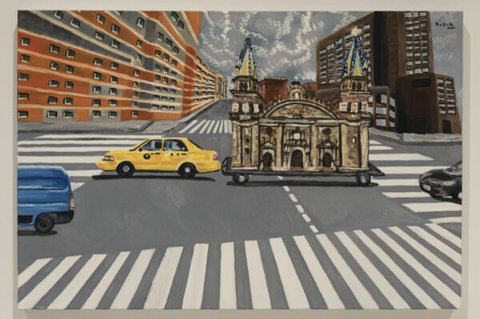

Metropolitan spaces like New York are centers of cultural, social, and economic prowess and growth. Such cities allow people to explore some of the greatest aspects of modern life. But among all the hustle and bustle, the millions of individual people, and the plethora of possibilities for what to do and who to be, city life can become oppressively overwhelming. There are a multitude of ways to handle the strain of urban living, and disparate coping methods are utilized in different ways, as evidenced by Regina Escobedo and Chaewon Lim in Dreamscape/Escape. High population density is an inevitable part of existing within a big city. In such environments, you are constantly surrounded by people, which creates two seemingly contradictory dilemmas: voicelessness–the sense that you are one small insignificant mass among all the other bodies–and loneliness–a feeling of isolation heightened by vast quantities of individuals who constantly surround you but with whom you have no personal connection. Escobedo’s artistic practice confronts these issues by asserting her individuality within her unique, painted depictions of New York, viewing each of her works as a self-portrait that resembles a journal entry. Her 2021 mixed media piece, “MY Times Square,’’ gives the viewer access to Escobedo’s mind, showing a fraction of the city through her perspective and providing a whimsical, dream-like escape from reality.

Inspired by the serenity of nature, Lim’s works provide a peaceful escape from the overwhelming, bustling city. She focuses on meditation in her sculptures as a means of creating this calming atmosphere. Mindfulness is an active part of her practice, from the art-making process to the interaction between art and audience. Lim practices mindfulness by experimenting with a combination of traditional and nontraditional materials, such as Korean Hanji paper and baking ingredients. She also utilizes minimal, solid colors to reduce the human-made quality of her works. Her sculptures instill tranquility in the viewer, but, when considered within the context of their display in a metropolis, they also connect nature to the anxieties of city life. The focus on nature in Lim’s works and their relationship to New York City evokes environmental-related issues present in large cities such as rapid urbanization and living in a fabricated environment. Lim’s minimalist works provide a means of escaping those concerns by returning the viewer to the calm of a natural environment and by encouraging internal reflection.

While Lim’s works are more compositionally simplistic, focus on nature, and provide the viewer with a sense of calm, Escobedo’s works are more compositionally elaborate, primarily focus on city life, and endow the viewer with a sense of surrealist wonder. Despite these differences, their artistic practices have a common ground: they both employ art to cope with city life. Dreamscape/Escape puts works by Escobedo and Lim in conversation, raising questions about how living in one city can create a similar need for escapism, and how that necessity can be mediated through entirely different practices.

Nature v.s. Nurture

March 1 – 4

Elsa Stern & Echo Yan

Curated by Kathryn Svensson

Nature or Nurture? The long debated question may be more aptly considered today in the struggle to overcome internalized thoughts and behaviors— residues of previous generations—that no longer serve to benefit our ever expanding world. Both artists explore this terrain of the normative, the internalized truths that guide us through our daily lives and influence the meanings we derive from our experiences, through the corporeal; their insides come out to challenge our conception of the ‘obscene’, ‘proper’ behaviors, and our anthropocentric tendencies, all of which are intimately intertwined with our society’s patriarchal, heteronormative, and white supremacist foundations.

Elsa Stern captures the discomfort created by the disjuncture between the nurture of the normative and the nature of knowing ourselves through images of motherhood, infancy, and wounded bodies. In her Untitled painting of a collapsed, downcast, pregnant mother, whose transparent belly reveals the life inside her tugging at a wishbone, Stern alludes to an underlying conflict between parent and child: the wishes and hopes, of the parent for their child’s life, and the child’s own wishes and hopes for them- selves. Similarly, in her painting Scary When Made to Treat Opinion as Fact, a heteronormative love story illustrated with chalk drawings surrounds a mother caressing her daughter’s hair. The young girl reads, ignoring her mother’s hetero-normative ideation, indicated by the scene between the girl’s legs which clearly shows two girls holding hands in a heart. These conflicting sides struggle against each other in a battle of prominence, leaving scars and war wounds, exemplified by Critical Hit’s memento mori.

Echo Yan’s work also considers both the formation of the self and the meta- morphosis of the body within specific contexts, examining it physically and metaphorically. In works such as Mutterleib, German for womb, a 3D printed infant lies in a curved container; they are surrounded by various independent, cylindrical swirls, brushed with the blood red of the veins, evoking used-tampons. Through the distorted womb and its discarded materials (infant and tampons), Yan attempts to destabilize our notions of the female body by conflating creation and destruction of-life and non-life-pregnancy and period. Yan’s piece Please Do Not Feed, a menacing mask with an outstretched tongue accompanied by pencil drawings of skulls in profile, exemplifies how the human body was domesticated, in the same way that animals have been, and physically changed to adapt to social societies and communal living: we no longer resemble, or need to be, the fierce predators that our ancestors once embodied. By equating this human and animal process of trans- formation, Yan confronts the viewer with their animality and causes them to question the validity of our distinctive hierarchy of beings, which places humans at the top and positions them as completely separate from other living creatures.

Ultimately, Stern and Yan’s works ask us to re-examine how normative modes of nurturing, and the subsequent internal biases we acquire, impact the elusive ‘human condition’ and the repercussions of our overwhelmingly anthropocentric mindsets.