The curatorial collaborative is a student initiative that brings together MFA and BFA candidates, as well as MA and Ph.D. Candidates in art history, allowing artists, curators, and art scholars to work together to create a final project, which is exhibited at 80 Washington Square East.

Sense and Insensibility

February 7 - 10

Jongho Lee and Daniel Evanko

Curated by Jiajing Sun

It is a pure accident that Jongho and Daniel both work with glass and metal but achieve disparate ends, stripping down disguises and obstacles in contemporary society. Objects are saturated by images and sound that always serve a designated public service. It is appearances that narrate the story, not humans. Guy Debord predicts our modern dilemma by saying, “everything that was directly lived has moved away into representation.” The exhibition Sense and Insensibility, featuring new works by Jongho Lee and Daniel Evanko, takes an initial step to retrieve our autonomy of time and sense, which have been clouded by seemingly or acoustically bewildering reality.

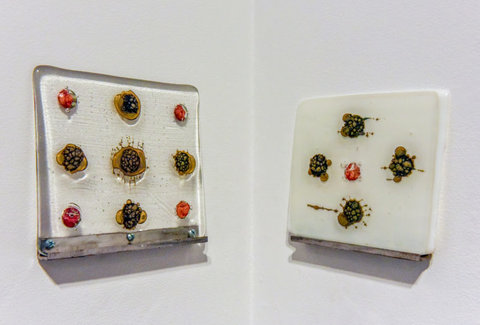

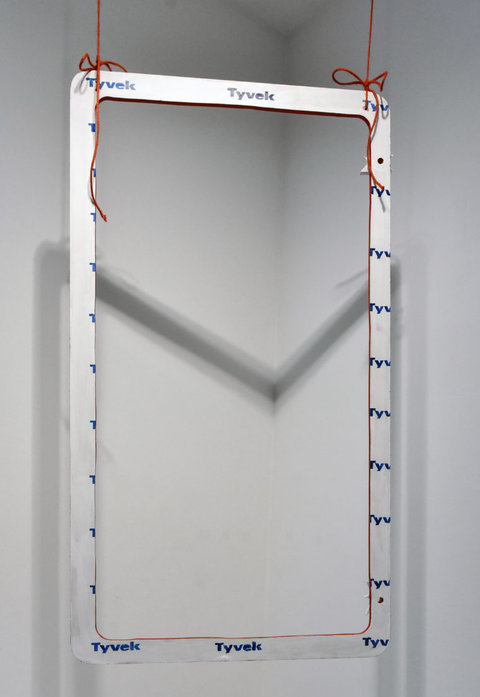

Jongho ceaselessly de-contextualizes found objects through a series of assemblage, alteration and re-installation. Abandoned window frames, wasted construction material, plastic knick-knacks and other frivolities — we are so accustomed to using and discarding them in daily life that we take for granted their predetermined functionality, readiness and harmlessness. His work, 9th and Stuyvesant, is a site-specific installation that prompts us to contemplate our abiding sense of security in urban environments. Jongho installs the metal pole in a way defying its normal presence. By doing so, he is able to re-shape its physical environment into what he calls an “architecture as deus ex machine in art form”, which evokes an eerily shocking effect as we gape at and evade it. His glass-metal sculptures also resurrect picked-up material from the street. After meticulous study of their chemical ingredients and manufacture profile, he alloys them. In the process of melting, deforming and forging, their own chronology as functional items shatter, thus giving birth to an alternative narrative of object history.

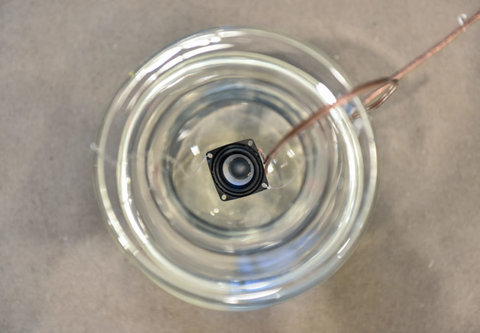

Daniel takes his cue from the immaterial sensorium that governs human interactions in our society growing ever distant and split. A musician his entire life, he believes that sonic elements, generated through or enhanced by sculptural objects, contain the decisive power to unify and resonate experience among the viewers. Connectivity is the penetrating theme in his works. A collectively shared experience of the sensorium can be reached only when inside the gallery space, which filters out the ubiquitous noises and hums of the city. Similarly exploiting the unpredictable materiality of glass and metal as Jongho, Daniel documents the incidental cracking as well as planned synthesis in the process of making. Material transformation alludes to the fluctuation of human psychological responses, which have long been waylaid and diluted by excessive stimulators in contemporary life.

The exhibition explores the full potential of spatial features at 80WSE Gallery, creating an sensorium immersion yet simultaneously disconnecting from our common knowledge of time and sense. Exemplified by the works of Jongho Lee and Daniel Evanko, we see a tension between the palpable objects and the formless, pure experience.

Signs as Places

February 14 –17

Olivia Chou and Marta Murray

Curated by Mengyao Wang

MOTHER TONGUE / LENGUA MATERNA

February 21–24

Catalina Granados and Elexa Jefferson

Curated by Amelia Russo

Anyone familiar with Google Translate’s mobile app camera function can avow

the awe of witnessing words morph fluidly between languages. In presenting a formal

conversion of letters alongside an exchange of meaning—and executing this in real-

time—it suggests that viewing the world through this lens can translate differences. And yet, is translation that straightforward? Is understanding that simple?

Catalina Granados’ and Elexa Jefferson’s artistic practices center these queries. In

analyzing the whys, hows, and so whats of the transition of something from one form into another, they probe the mechanisms we utilize to convey, transfer, and interpret meaning between each other. Whether in a linguistic or cultural context, each artist surveys translation’s resonance within the roles we uphold in society.

In her new work, 06200, Granados pushes into social practice and collaborates

with an elementary school drama class in Tepito, Mexico City. She coordinates

expressive forms—video chat, written letters, and drawings—in the exercises she conducts with the students to explore fear’s manifestations in their (daily) lives. Ultimately, Granados will create a personal costume for each child that, when worn, will render her invincible to her fears.

Granados evinces language’s limitations. 06200 elucidates the futility of linguistic

translation to cross between artist, participant, and viewer; too much is lost and

differences are distorted, yielding an unfaithful translation, a false facsimile. This ethical question of translation authenticity corresponds to Tepito’s street market, where many of the students’ relatives earn their livelihoods. There, one product formerly sold (locally manufactured shoes) has been substituted for its copy (counterfeit designer sneakers), making visible the transformation of one means of production from its original state to its duplicated, illegal version. Granados examines the ideologies driving this phenomenon, their emotional ramifications, and their transmission through older generations to today’s youth.

Jefferson engages different modalities of translation to test the processes’

concentrative qualities. Inspired by R.D. Laing’s poems referencing psychiatrist-patient conversations, Jefferson investigates the convention of ‘translating out’ to generate additional significance. Just as the rhetoric of therapy transfers into verse, Jefferson extracts phrases from a 1945 radio play script and recontextualizes the distillations in Rocket from Manhattan (September 20, 1945). Exploring material and process, Jefferson manipulates her wooden sculpture to resemble sheet metal onto which she engraves the text-based pastiches.

The words, and their inherent meanings, serve as Jefferson’s found objects, which

she layers and links into revised narratives. For her, this act of omitting text and

restructuring excerpts operates parallel to a car radio’s scan button, which stitches song

and broadcast segments into a continuous stream. In Rocket, Jefferson captures a different essence of meaning and imparts ruminative statements: “We left of life something more than a confused dream.”

Just as a slight waiver of the hand renders the translation on Google’s app momentarily indecipherable until the words recalibrate, understanding is something we

can find and lose. Granados and Jefferson both make art that seems confident we can find it, but reminds us that we need the nuances of translation to enable genuine

comprehension.

Do You Begin Where I End?

February 28 – 3

Lilli Biltucci and Monilola Ilupeju

Curated by Sam Allen

Does it signify something politically meaningful to cry over art? I’m not talking about that threadbare sentimentality of being overwhelmed by beauty but something altogether different, more modest perhaps: a feeling-with, mediated by an artwork, that draws you to the outer reaches of yourself and puts you in contact with another person. In “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Audre Lorde is explicit about the political stakes of such empathic connections, writing, “The sharing of joy . . . forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them, and lessens the threat of their difference.” This experience of commonality and difference-through- sameness clarifies the contours of relationships to the surrounding world. Occasionally it can infiltrate spectatorship, taking the form of feeling seen by, feeling in sync with an artwork. Stemming from a blend of gratitude for a brief moment of intersubjectivity and frustration that, despite it all, we can only understand one another

to certain limits, to cry is to yearn (productively, if you choose) for such relationality to take root beyond the walls of the gallery space.

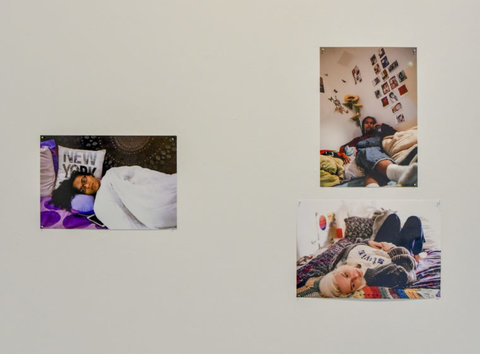

I begin here because the first time I felt in sync with the work of Monilola Ilupeju, as

well as with that of Lilli Biltucci, there were tears. This experience clarified my sense of

these two artists’ projects. Ilupeju operates with so acute a directness — whether in

monumental, meticulously painted self-portraits or confessional videos dexterously

produced with insufficient digital tools — that one doesn’t realize until it’s too late how

the work has radiated concentrically out from her own experience of dysmorphia and

other physicalities to encompass the viewer within a space of shared experience. If these

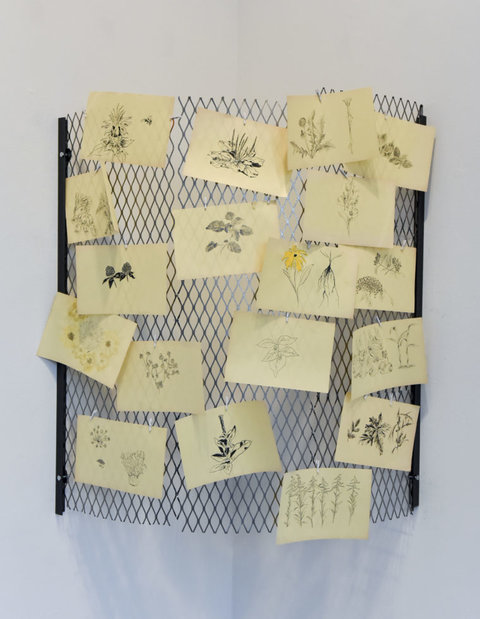

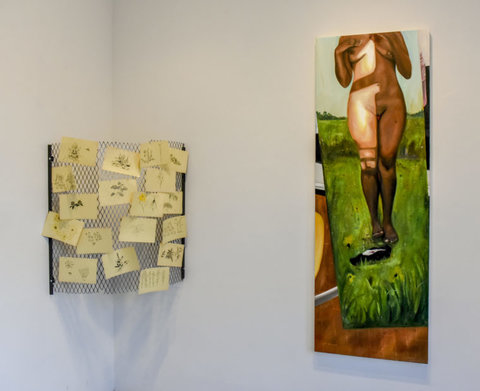

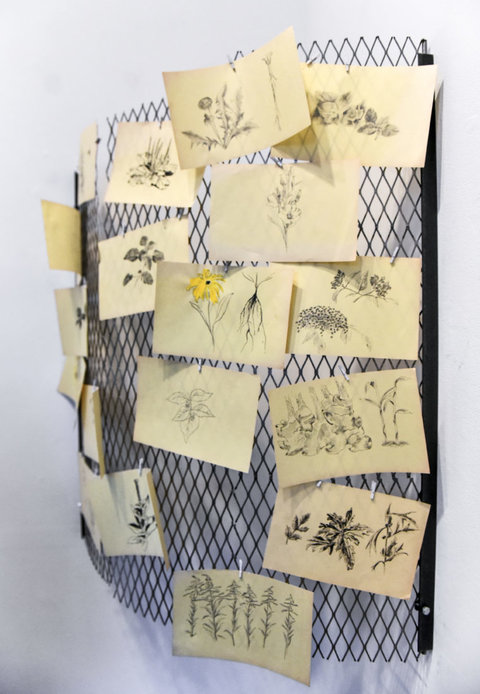

pieces encounter their audience with an embracing action, Biltucci’s art operates more along the lines of a constellation. They hang shelves of soothing flowers and spices, gift hand-sewn jumpsuits to friends, redistribute the resources and platform that accrue to one who calls themself an ‘artist:’ antimonumental acts generating vectors of transmission that aim to undo the reductive singularities of a world masterfully ordered by power — reducing objects to exchange-values, artists to self-sufficient actors, people to bounded and stable identities — minor acts of exchange that hope to map escape routes from the rigid binaries these pieties produce.

Issues of gender, sexuality, and race lie at the heart of both artists’ practices, and in both

cases we might speak of an aesthetics of vulnerability or radical honesty, of a turning

outward of their interiority to turn it into a vehicle for building coalitions around the

experience of living. Do you begin where I end? combines the enclosure of an embrace

with the interlinking of a constellation to form a provisional space that privileges the

intimacies and the exchanges (of ideas, memories, intentions, care) that accompany

collectivity. By reframing the creative act as participatory, Ilupeju and Biltucci generate

opportunities for affirmation and sustenance, for seeing and knowing others, and for

understanding more clearly — through empathy — the contours of our contact with the world.

Body Building, Body Blurring, Body Breaking

March 7 –10

Jackie Kong and Nathan Storey Freeman

Curated by Phoebe Herland

Jackie Kong and Nathan Storey Freeman both approach art-making through regimented exercises and performance pieces, aimed at deconstructing movement, images, and paradigms therein.

Kong spent her formative years at the barre of a ballet studio, pointing, stretching, repeating, perfecting. Her work continues to engage with and regulate the body sometimes her own body, sometimes the bodies of her peers, often negotiating the boundary between the two. In a 2015 series of 50 choreographed instructions, she condenses movement into sparse directions:

1. Choreography in four parts (1)

2. Hand on your hips

3. Heels touching

4. Bend your knees

5. Straighten your knees

The simple, organic gesture is deconstructed and reassembled in language. There is room in this translation for misinterpretation. Indeed, she invites the viewer to transgress the classical ballet of her youth, opening it to the masses. The tidy compartments of her conceptual project are muddled through

their various and numerous interpretations. Her more recent work calls for viewers to enact change upon her own body, further problematizing and blurring the body and its autonomy. Reversing traditional roles,

the viewer’s body becomes active while the artist’s body becomes passive, while still retaining authorial voice.

Similarly vested in the body, Freeman’s work interrogates the concept of masculinity and the veracity of its image. Indeed the image itself, as he positions it, is gendered with male pronouns. Through relentless reproduction and dissemination, the photographic image constructs damaging masculine paradigms for its fellow male bodies. Part III of Freeman’s thesis is titled “Guidebook: How to Destroy Image, Language, and The Male Body.” Under the heading “Men’s Health Magazine November 2017 Edition,” Freeman instructs the reader to:

I. Purchase the magazine for $4.99

II. Read the magazine in full however do not read the last page

III. Place your fingers on the men’s faces on their fingers

IV. Prepare the fork and knife

V. Cut the bodies out of their home

VI. Re-structure an image that has never existed, could never have existed

VII. The boys are so tickled, a home away from home

That these instructions are at times impossibly specific, at times confusingly vague, mirrors the way Freeman believes images direct us and trap us. In his work, Freeman actualizes this process. He accumulates words and images, feels for their boundaries, cuts them out, displaces their contents, examines their innards, and assembles them on walls– a home away from home. In doing so, he transitions the men of item III to the boys of item VII. Thus, the image he reconstructs is an innocent one,

a de-socialized one, a queer one.

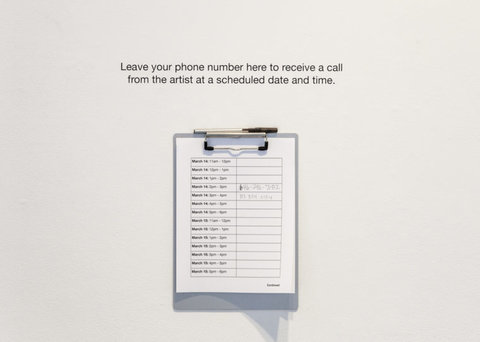

Kong is not interested in destroying media so much as slipping its noose altogether. Unlike

Freeman, her performance pieces rarely leave residue beyond a drawing in a private notebook. In fact, there are hardly any objects in this exhibition at all, only a clipboard facilitating Kong’s conceptual piece and the wall-bound assemblages contributed by Freeman. The walls, too, may have been deconstructed by the artists had they not been structurally necessary.