The curatorial collaborative is a student initiative that brings together MFA and BFA candidates, as well as MA and Ph.D. Candidates in art history, allowing artists, curators, and art scholars to work together to create a final project, which is exhibited at 80 Washington Square East.

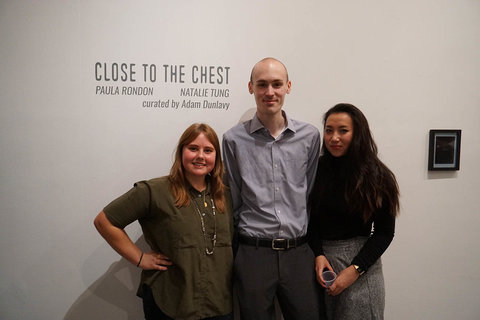

Close to the Chest

Paula Rondon and Natalie Tung

Curated by Adam Dunlavy

Paula Rondon’s sculptures meet many of the

expectations an art audience has for contemporary sculpture in 2016: unconventional materials arranged

in space, a distinctive eye for color. They even reference art history, pointing to an assemblage tradition from Ed Kienholz to Rachel Harrison. And, like Kienholz’s landmark installation Roxys (1960-61), there seems to be an implied narrative. The sculptures look like characters, and the compositions like tableaux. The titles further the impression, until you “get” it: an “aha” moment.

Rondon draws imagery from films so classic that they have entered the public domain of the collective unconscious: Dirty Dancing, The Graduate, Titanic. Already-seen, already-parodied, the scenes she uses

are immediately recognizable. Two buoys become Jack and Rose at the bow of the Titanic. But Rose is wearing floaties, doubling down on her already buoyant rubber body, as if Rondon could still change the plotline, presenting Rose as humorously overprepared. And yet, despite the pathos of her surrogates and the familiarity of her plotlines, Rondon’s sculptures are not quite figurative. Rose is still a buoy pierced by banisters. The sculptures are freeze-frames, locked in perpetual climax, like actors cueing for the director to call action.

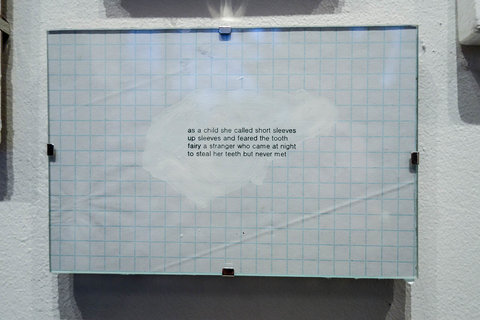

Natalie Tung’s images arise from a solitary process. She lies in bed, watching nighttime pass, waiting for duration to give way to stillness, and stillness to give way to sensitivity. In the vein of Andy Warhol’s eighthour, single-shot film of the Empire State Building by night, Empire (1964), the sense of nothing happening falls away, and subtler occurrences coalesce. Cars pass by. Headlights trace paths of light through her blinds and across the bedroom wall. Each leaves an imprint on memory: an afterimage. Slowly, the room becomes a kaleidoscope of new and half-remembered visual phenomena. These are the moments Tung photographs.

Curating from among hundreds of these nighttime documents, Tung then prints and scans the most dynamic examples with a handheld scanner. Turning the prints and swapping them for others mid-scan,

she casts one more trail of light and conjures an image of that kaleidoscope. Points of time collapse into undifferentiated experience. Like Tony Smith’s drive on an unfinished highway, the constancy of the bedroom, like the unmarked pavement, conflates points in time and space. But this is a fragile, un-nameable feeling, stretching language to its limit. You can experience it, remember it, but are never quite sure it’s more than in your head, because of course it is.

Rondon withholds all but the most iconic details of a scene. Abstract ideas are not the hidden content of apparently mass cultural imagery. Blockbuster films are the hidden content of apparently abstract sculpture. Her work gathers its force from our image-saturated culture, playing off images we have already seen innumerable times. Tung leaves unsaid what can’t be said in the first place. By withholding optical interest, her images become as still as a mirror lake. Our attention is drawn to the slightest ripple, diffuse, half-remembered and already vanishing. Tung suggests that the numbness produced by our endless flood of images could be the ground for heightened sensitivity. Both Paula Rondon and Natalie Tung withhold not to refuse meaning, but to explore the particular meanings made possible by their silence.

Dialectic Recollection

Annie Carroll and Tritia Lee

Curated by Rachel Vorsanger

Author William Gibson said, “time moves in

one direction, memory another.”1 Yet, how separated are our memories from daily life? How often in our present realities do we slip into moments and emotions of the past?

Dialectic Recollection is an exploration into the past that pulls at us and the emotions it elicits. In their work, Annie Carroll and Tritia Lee have each imposed their own process to understand this cycle of memory. By harnessing personal experiences and transmitting them to tangible representations, their works become physical manifestations of their conversations with memory.

As a painter, Annie Carroll thrives off the challenge of showing the importance of oil on canvas in today’s digitally-dominated world. Based on personal narratives and found photographs, her work fuses figurative elements with intriguing distortions. Finding this newly abstract aesthetic has made her contemplation of nostalgia and loss a universal narrative.

Through an introspective examination of

the past, she reconciles the willful magnetic force that draws us to indulge in certain memories. Tritia Lee’s work can be categorized neither as painting nor sculpture. Her unique aesthetic is the result of rubbing charcoal onto fabrics when laid against certain chosen surfaces that range from corners of rooms to the ground in a public park. These rubbings are made on sites that the artist has previously experienced and chosen purposefully for the significance of the emotional attachments found there. The final results are tied as equally to chance as they are to her control: Lee will not know the outcome until she displays the fabric over her hand-crafted wooden beams. She evokes the ephemerality of memory through her materials, which she sews together or drapes off the wooden frame upon which they hang. She constructs new architectural spaces created by emotions from memories, and by juxtaposing structure and organic, has found a raw and delicate aesthetic.

Carroll and Lee are visual storytellers, translating emotions into tangible records of paint and canvas, and charcoal and material. Together, their works enter into a dialectic conversation about the emotions elicited from the processes of remembering and forgetting. While it is the emotional that drives each artist’s process, the triggers for those emotions are juxtapositions in themselves: Carroll recalls intangible memory, Lee begins with the physical. They invite viewers to reflect upon their own present realities and nostalgic pasts when considering this dichotomy.

This show reconciles the paradox presented in Gibson’s quote by showing that our past memories and present lives are intrinsically intertwined. Our memories are layered one upon another, building themselves into our consciousness and influencing our actions. These works investigate the past in order to actively address and illuminate the enigmatic cycle of memory that is present in our everyday lives.

Dialectic Recollection presents all new works made by Annie Carroll and Tritia Lee, a testament to their dedication to this personal project.

eros // logos

Victoria Browne and Eda Ozdoyuran

Curated by Ellis Edwards

In 1935, Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger developed a thought experiment, a rather paradoxical one, on the state of quantum superposition. A cat is placed in a box. Also in the box is a vial of poison and a radioactive source. If even the smallest amount of this source decays, thus, emitting radiation, it triggers a hammer, which shatters the vial of poison, killing the cat. Outside of the box, the observer cannot know if the radioactive substance has decayed and, consequently, cannot know if the lethal vial has been broken. The cat is simultaneously in a state of life and death. It both is and is not dead.

How does Schrödinger’s cat from 1935 relate to a 2015 show of two Steinhardt honors students at the 80WSE Gallery at NYU? Similarly, Browne and Ozdoyuran focus on a central theme of the paradoxical. Both independently and collectively, when juxtaposed beside one another, their work is and is not what it claims or appears to be. Browne’s work, eros, is cosmic, intangible, and esoteric; Ozdoyuran’s work, logos, is concrete, political, and tangible.

Victoria Browne communicates timeless truths within contemporary contexts. She uses traditional mediums, along with performance, video, and installation. Browne’s daily spiritual routine, influenced by Raja, yoga, Zazen, and Kabbalah, becomes centrally integrated into her artistic practice. The exercises customary in these spiritual sects, which frequently involve entering a trance-like meditative state, reveal the paradoxes and unique phenomena of various occult traditions. Central to occult revival in contemporary cultures is an idea of political progressivism. The Rest Is Silence is a sound installation which features sixteen lecturers, ironically, discussing the value of silence.

Eda Ozdoyuran is intrigued by the unlikely unity of opposites. She embodies physical and perceptual paradoxes. Emphasizing the materiality of her mediums — wood, metal, cement, and found objects — Eda incorporates a concept of presence within absence. Two contradictory forces nestle within each other, while also propelling the tension between them. Ozdoyuran re-narrates and brings new meaning to the independent parts, while also re-establishing their unlikely combination. Unreturned depicts a caged minaret. Its crescent moon finial lies on the floor, attached to a chain. Here, Ozdoyuran highlights the strained political relationship and intense power struggle between the religion of Islam and the present state in Turkey. A surface reading of this exhibition would conclude that these artists’ work could not be more opposite the other. Upon closer examination, viewers see the creative harmony between Browne and Ozdoyuran.

United by an interest in the confusing and perplexing world of paradox, the artists invite the viewer to ‘go down the rabbit hole’ and question what lies beneath the surface of the systems which define contemporary political, social, and ideological norms.

Allure – Delicious and Profound

Dae Young Kim and Rebecca Salmon

Curated by Tiffany M. Apostolou

Imagine you’re exploring New York like another Odysseus, or Leopold Bloom – a modern day flaneur. Imagine now, that you come across a cave unlike any other you have ever seen, and in the middle of the city for that matter! There’s something about it that draws you in, stirring your curious side. It could be a sound, or just a sense – a sense that you simply must indulge in your curiosity.

Upon entering this mysterious cave you encounter a room full of strange, yet, not entirely unfamiliar objects. Are you supposed to be there? Is it permitted to poke around? Nothing is quite clear, but there is an allure to the space, and its objects that make it impossible to leave without knowing more. So you stay, and look at all the wonders in the room, having completely given in to their allure.

Rebecca Salmon is an artist whose flesh-like works play with perceptions of body, and gender rituals, raising curiosity through an initial shock. The gelatinous textural surfaces meticulously and painstakingly shaping the works she creates are embellished with

intricate details such as hair and even veins.

This heartfelt care for the texture, color and realism of these body-like works call the viewer, like the enchanting song of Sirens, to step out of their understanding of the body and become intimate with her life-like pieces.

By playing with ambiguous representations of flesh, and the understanding of what is real, and what is not, Salmon engages the viewer in a humorous, yet meditatively calming way. Lately, she has also been experimenting with sound.

Dae Young Kim has developed a sculptural, and drawing practice that evolves around the concept of curiosity, and the inner turmoil it causes. Borrowing from the idea of the Wunderkabinett, Dae Young makes large cabinet-like sculptures that offer halfhidden, half-exposed views of their mysterious interiors. This play between hidden and enclosed calls the viewer to physically interact, and examine the objects that appeal with the innocence of another Pandora’s box. Moreover, even his largescale drawings play upon the human need for clear answers. The carefully drawn, and blurred images envelop the viewer within their sphere of enchanting indiscernibility as one tries to make clear what he is and is not looking upon.

Both artists’ meticulous attention to detail reveal their own intimacy with their objects, one that becomes reflected upon, and shared with whomever steps into the wonder-full cave that exhibits their works. Their pieces, flat or sculptural, ignite an inner dialogue that creates a singular experience for anyone who gets entangled in their allure. In this interactive viewing process, what remains is a sweet calmness, unlike the inner stir created by the initial curiosity from first encountering their work.

no time like the present. for ghosts.

Susannah Liguori and Laura Pfeffer Curated by Kathleen Robin Joyce

“April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire”

— T.S. Eliot, “The Waste Land”

The transition from winter to spring negotiates a delicate interplay of loss and promise; the memory of a mitten dropped on the sidewalk is balanced by the potential of thawing earth. The objects around us become imbued with these losses and gains, indirectly representing people and places once cherished. The remnant, through its presence, seems to signal something — or someone — else’s absence.

While they work largely in different media, both Laura Pfeffer and Susannah Liguori have adopted the remnant as their primary material. The thematic affinity between their bodies of work is hardly surprising; the two artists have known each other for nine years. Through sometimes poignant but never precious work, Liguori and Pfeffer ask how it is that we come to value certain objects, navigating emotional bonds, absence, and absurdity.

“When you find a bobby pin on the ground,” says Liguori, “you don’t think, ‘Oh, this is from 1987!’” Divorced from their original context, the found objects in her work are timeless. Though they clearly once

had a use, their capture and preservation in vacuum-sealed bags render that purpose illegible, forcing the viewer to ask: what is it?

Their incomprehensible value produces a tension that animates much of her present work. Sometimes language itself is an

obstacle for Liguori: words become mere traces of meaning and are never sufficient. Recent works present facts about the artist and unanswered questions along with traces of our lives as consumers, specifically receipts and business cards. What is valuable information? What questions can be asked, or answered?

Pfeffer puts found objects to work, producing videos that bear the trace of the Internet even though they circulate as fine art. Operating in the space between fiction and nonfiction, Mollie’s Interview repurposes found footage of upstate New York — fragments of the lives of strangers — to “illustrate” the childhood home of Pfeffer’s friend, Mollie. A new, parafictional purpose is inscribed on these digital remnants, estranging them from their original context. Pfeffer’s works produce a dislocating dissonance that is sometimes quite funny: absurd and selfdeprecating humor are prominent in her oeuvre.

In addition to her practice as a video artist, Pfeffer has recently begun producing soil. She composted the soil in her contribution to the collaboration with Liguori using food waste from her friends and loved ones, including Liguori and myself. This act gives material presence and heft to the intangible bonds she shares with them. Once waste, the traces of these people have a second life in this space, charged with the potential for new growth, mixing memory and desire.