MFA candidates in the Studio Art program work alongside faculty, visiting artists and art professionals to create a series of group shows, which are displayed at 80 Washington Square East.

with:

Stephen Gurtowski

Harry Kleenman

Caitlyn Mclaughlin

Marz Saffore

Gabrielle Vitollo

Stephen struggles with painting, in a productive way. His paintings find their way into being, one imagines, through epic sessions that could, at a certain stage, involve stepping aside and letting the painting itself figure out what it wants to be. In that scenario, there’s the painter, going at it, full of ideas and books open on the table but not knowing how any of it actually relates or if it will come together. One must forge on in this pursuit, which involves nothing less than the production of knowledge.

One from the next, the paintings are quite different—at least that’s my impression because I haven’t seen a body of work all at once. It’s usually one or two at a time in the studio. With each new work I sense Stephen struggling to see the work at all—how far back must we be in order to convert subjective engagement to objective observation? What ineluctable lag is it that promises such perspective?

Something he said the other day in a studio visit—he wanted to make a really hard painting—stuck with me. Hard for whom, I wondered. There’s more than enough doubt to go around. That seems to be an aspect of contemporary painting today—pervasive doubt and uncertainty—it’s like a shroud. You hear them say that painting can’t be authentic anymore in the industrial art complex. You know that painting seems more and more anathema to digital culture. Hard painting—in Stephen’s studio the other day it felt like Cobra painting from the late ‘40s and early ‘50s. Like Dubuffet’s “l’art brut.” Very urban. Very mental. Experimental—just you and the blank surface, the weight of history, and heaps of expectation: Just what painting is and potentially will continue to be.

Here are some considerations about Harry’s work. There’s smell. There’s funk. There’s apparently little skill on display. There’s bricoleur panache. Add to that a dedication to material decadence, a penchant for dilapidated elegance, and an extremely pronounced sense of enfeeblement when it comes to craft. And it works! In the vein of Franz West and Arte Povera artists, Harry’s sculptures arise from everyday materials and situations that are subjected to different types of “art treatment”—fermentation, paper making, mold making, coating, decorating, etc.—and that result in very familiar yet fallible sorts of objects that proclaim usefulness but decline any function. Decorative flourishes abound and failure—as a kind of goopy, soft, prolapse event--is celebrated. The studio is rich with the loot of the streets, which is where the referential heart of the work lies. It suggests a life of the artist as a kind of vagabond, a “ragpicker”—or have we gotten carried away with the economy of the work to conjure all kinds of adjacent contents? Boris Groys’ suggestion in “Post-Production” of the artist as rummaging through the flea market of history comes to life in Harry’s studio practice.

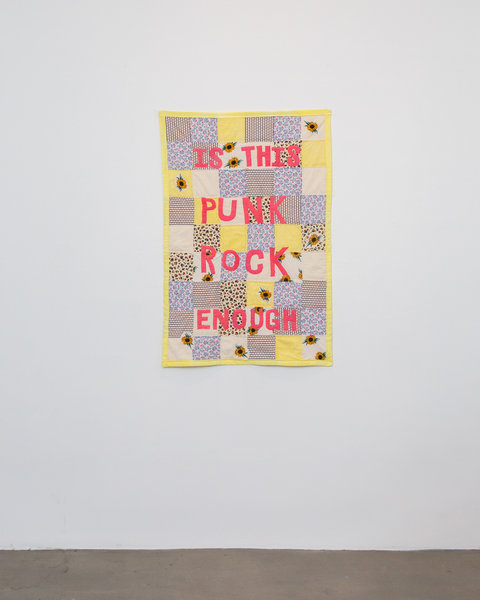

Who knew “classical Feminism” was still so challenging! Caitlyn takes a stance that reverberates with what amounts to a type of militancy but there’s nothing vintage about it. She makes quilts that emblematize references to traditional femininity, and simultaneously complicates that reading with appliques that are meant to be provocative and combative—“Is this punk enough for you?” Working with quilting and other “needle arts” Caitlyn has found her way into rich formal territory that may or may not be endowed with specific content—except, of course when activated by text, which often bristles with bombastic edge. In one sculpture, she combines wooden elements that conjure a girl’s bedroom with knitted panels ornamented with tiny letter beads. Upon close inspection—you have to get right down on it--they castigate shallow attitudes and speak about transgression.

Knitting, macrame, embroidery, sewing—the hand is central, as is the body, to the work. Comfort is paramount, but so is some notion of excess. She pushes to the limits of a material, knitting rubber tubing for example, or making curtains of extremely delicate knotted threads. In Caitlyn’s work, time and labor are materialized—not necessarily in the historical sense of “women’s work” (really, how many women produce quilts or knit or sew these days—except recreationally). Rather, the time invested in her sculptures resonates as a critical practice, but not one bound necessarily by gender. Solitude, mental expansiveness, experimentation—these are cornerstones of her practice, but so, too, are explorations of personal space, intimacy and comfort.

“Let’s De-Colonize This Place” –- I saw that “bumper sticker” on Marz’s door before I met her. It read loud and clear: social practice at work here. What place, in particular, is “this place” I wondered. NYU itself is an obvious place to begin, but one institution begets another, from the academy to academia, from the site of the exhibition to the distribution network, and from the discourses of art to its markets and audiences. Everything is potentially up for review. Socially motivated practice is, by definition, self-conscious. Where does it fit within art’s economies? Who is the primary audience? Is there a goal? A message? A vital “take away”? Here, in the wake of many waves of multi-culturalisms and post-colonialisms, we have all become extremely aware. An art of protest? It all has to be re-invented, from the ground up, with each generation asking hard questions, probing the social conscience of art and the art world, and figuring out positions.

“Social practice” is one of art’s reflex mechanisms. It’s always about the people but rarely for the people. And on the horns of that dilemma, Marz begins to gain traction as she explores visual politics. She’s in a unique position, along with other socially–minded artists of her generation, to appreciate the complexity of the present. Particularly in global art culture, economic divides are more egregious than ever before. Good intentions are often distilled as “expressive elements” and narratives of struggle are easily commodified—the problem is that there are almost too many historical precedents and models for socially engaged practices today.

Is there a divide between collaborative and individual practice? How do we negotiate activism and object-making? Given that these have been concerns throughout modernism, it would seem imperative that contemporary artists take up the gauntlet, but to what end? What’s at stake extends far beyond objects made in a studio, but that is as logical a place to begin as any.

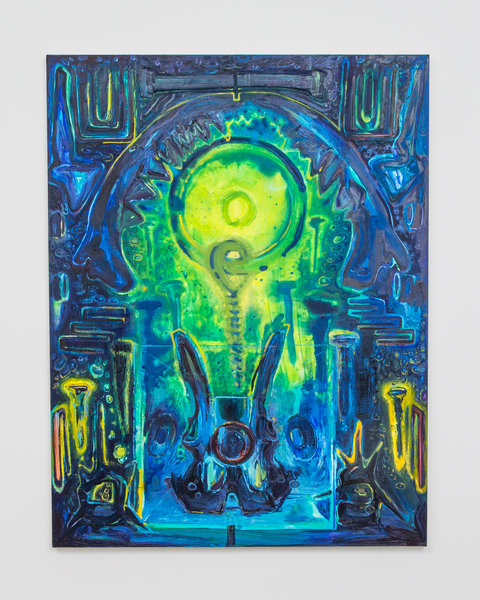

Walking into Gabrielle’s studio is like walking into a fiercely exotic, techno-futurist time zone (somewhere between here and there) that borrows from science-fiction and ethno-anthropology on its way to over-whelming the viewer with sheer scale and material diversity. Whether in big muscular paintings, delicate etchings, digital photographs, gelatin sculptures or even colorful cactus gardens, the futuristic and the oddly antiquated intertwine and energize to bedazzle the viewer with a sustained color-infused sensual overload. Motifs are shared, whether animal bones or antique tools, and are often arranged as contemporary “detritus fractals” in whose profusion we delight.

There is also plenty of undertow in the work. The paintings, activated by heroic scale, scream with energy: color is keyed to a constant high pitch, tidal waves of gestural imagery roar across their emboldened surfaces. The repetition of forms—things as simple as old square nails or metal staples—march in unison across surfaces and suggest an arcane hieroglyphics, like a cultural language gone extinct.

The sublime is front and center in Gabrielle’s work. It’s informed by Romantic painting, by Abstract Expressionism, by CGI cinema—oh, and let’s not forget “real life” dilemmas that rim our existence and threaten widespread extinctions. Don’t look now, but Gabrielle makes art for the Anthropocene—annihilation anyone?